자가재구성 가능 생산시스템을 위한 목적모델 개발

© 2021 KIIE

Abstract

A fractal manufacturing system (FrMS) is one of the most advanced and self-reconfigurable manufacturing systems among the available manufacturing systems, which is based on the concept of autonomously cooperating agents referred to as fractals. In order to determine and generate goals or objectives, the FrMS use goal-orientation mechanism which includes goal-formation process (GFP). Generating goals as well as sub-goals requires a model defined from mutual relationships or networks among various objectives such as productivity, quality, and etc. However, previous research studies have not yet defined such discussion regarding mutual relationships among goals or sub-goals. The goal model is crucial in order to change the final goal in the manufacturing system. Therefore, this paper, proposes the development of a goal model for the FrMS by analyzing former objectives/goals while obtaining a new goal from manufacturing datasets. The result of goal model for FrMS is not permanent, but it is adjustable based on the changing environment. If the final goal changes, then lower-level goals will also change to help achieving the new final goal. The proposed mechanism for the goal model is developed to complete and support the goal-orientation technology by adjusting company’s goal. The proposed goal model provides a basis for flexibly changing system’s goal in the manufacturing system and proposed model enables faster response to cope with changing goal by system’s requirement.

Keywords:

Fractal Manufacturing System(FrMS), Goal-Orientation Technology, Goal Model, Goal Model Mechanism, Self-Reconfigurable Manufacturing System.1. 서 론

생산시스템은 급변하는 시장에 대응하고 글로벌 경쟁력을 강화하기 위하여 많은 변화를 거쳐 왔으며 이는 유연 생산시스템(Flexible Manufacturing System), 린 생산시스템(Lean Manufacturing System) 등과 같이 생산시스템의 지능화, 적응성 등의 발전을 이루어 왔다. 하지만 나날이 다양해지는 소비자의 요구와 하루가 다르게 변화하는 기업 환경은 보다 뛰어난 생산시스템을 원하고 있으며 이러한 요구에 부응하기 위하여 많은 연구자가 차세대 생산시스템에 대한 연구에 몰두하고 있다. 현재 연구를 진행하고 있는 차세대 생산시스템은 여러 가지가 있으며 그 중 몇 가지를 살펴보면 생물학적 생산시스템(Biological Manufacturing System; BMS)(Ueda, 1992; Okino, 1993; Ueda et al., 1997), 홀론 생산시스템(Holonic Manufacturing System; HMS)(Seidal et al., 1994; Valckenaers et al., 1994; Brussel et al., 1998), 프랙탈 팩토리(Fractal Factory)(Tirpark et al., 1992; Warnecke, 1993), 프랙탈 생산시스템(Fractal Manufacturing System; FrMS), Ryu et al. (2001), Ryu and Jung(2002, 2003) 등의 연구가 있다. 본 논문의 대상이 되는 FrMS은 전형적인 자가재구성(Self-reconfigurability) 특성을 갖는 생산시스템으로, Warnecke(1993)가 제안한 프랙탈 팩토리 개념을 Ryu and Jung(2003, 2004), Ryu et al.(2006)이 한 단계 발전시킨 것이다. 그리고 이를 바탕으로 하여 Shin and Jung(2006), Shin et al.(2009, 2012), Shin and Ryu(2013)는 r-FrMS(Relation-driven Fractal Manufacturing System) 등 관련 연구를 진행한 바 있다. 이 밖에도 Renna and Ambrico(2011)는 FrMS의 프랙탈 컨셉을 활용하여 동적인 상황에서 셀룰러 제조시스템(Cellular Manufacturing System)의 시스템 효율성과 생산성을 높이기 위한 연구를 진행하였으며 Attar and Kulkarni(2014)는 FrMS의 장점과 효율성에 대하여 리뷰를 하였다. 그리고 Mandal and Sarkar(2014)는 FrMS을 포함하여 현존하고 있는 생산시스템간 비교를 통하여 각 시스템에 대한 장점에 대한 연구를 수행하였다.

생산시스템의 목적 및 목표에 대한 기존연구는 이미 정의 및 조직화되어 있다는 가정을 바탕으로 문제의 해결 방법 도출에 집중하였다. 생산시스템의 다양한 목표(Objectives)는 연구에 따라서 한 가지 목표에 대한 최대화, 최소화 혹은 다수의 목표에 대한 최적화를 이룰 수 있도록 각 연구 마다 제한된 목표만을 대상으로 하였다. 이에 따라 제한된 생산시스템의 목표를 대상으로 한 다양한 방법론이 개발되었으나 대부분의 방법론은 수시로 변화하는 생산시스템의 목적을 실시간으로 반영하지 못하며 생산시스템의 목적이 바뀔 때마다 이를 위한 방법론 역시 바꾸어야 했다. 이에 반하여 Ryu and Jung(2006)의 목적 주도 기술은 조직화된 목적(Goal)을 환경 변화에 따라 자동으로 생성하는 문제를 다루었다. 목적 주도 기술은 3단계로, 목적을 생성하는 목적생성 프로세스(Goal-generation Process; GGP), 목적간 충돌을 회피하고 조정하는 목적조화 프로세스(Goal-harmonizing Process; GHP), 그리고 목적간 균형을 조절하는 목적 균형 프로세스 (Goal-balancing Process; GBP)로 구성되어 있다. 그리고 Shin et al.(2006)은 목적주도(Goal-orientation) 기술에서 목적조화 프로세스에 대한 보다 구체적이고 자세한 연구를 진행하였으며 Cha et al.(2007)은 목적균형 프로세스에 대한 구체적인 연구를 진행하였다. 목적주도 기술의 기존 연구는 FrMS에서 각각의 프랙탈 유닛이 하나 이상의 목적 및 목표를 가지고 있을 경우와 하나 이상의 프랙탈 유닛의 목표가 서로 충돌, 상반될 때 이를 해결할 수 있는 방법론을 구축한 것이다. 이와 같은 방법론을 구현하기 위해서 Ryu and Jung(2006), Shin et al.(2006), Cha et al.(2007)은 퍼지 개념(Fuzzy Concept)을 도입하여 목적 및 목표간 충돌을 해결할 수 있는 방법을 제시하였다. 하지만 목적모델에 대한 연구는 참조 모델(Reference Model) 제안에 그쳤으며 목적간 관계에 대한 연구는 매우 미비한 상황이다. 또한 생산시스템의 목적은 목적간 상호 의존성과 복잡한 연관관계를 가지고 있으므로 이에 대한 연구는 쉽지 않다고 하였다. 따라서 목적모델에 대한 연구는 아직 진행 중이라고 할 수 있다.

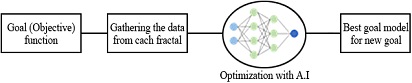

본 논문에서는 목적주도 기술에 필요한 FrMS 목적모델과 이를 도출하기 위한 일반적 목적모델(Generic Goal Model)을 제안한다. 목적주도 기술에 필요한 목적모델을 도출하기 위하여 우선, 기존 생산시스템의 목표(Objectives) 및 목적(Goal), 평가 항목을 조사하여 생산시스템이 가질 수 있는 생산시스템의 일반적인 목적모델을 도출하고 이를 통해서 FrMS에 적용할 수 있는 목적모델을 생성 및 제안한다. 제안된 FrMS 목적모델은 정형화된 구조가 없으며 생산시스템의 특징과 최종목표에 따라서 변화할 수 있다. 최종목적에 따라서 프랙탈 유닛은 최종목적을 달성할 수 있는 세부목적을 설정하고 상위목적과 하위 목적간 관계를 정립한다. 각 목적간 연관관계를 도출하기 위해서 통계적 기법 중 회귀분석을 활용한다. 이를 통하여 최종 목적에 부합하는 하위 목적을 설정한다. 제안된 목적모델은 신경망(Neural Network)을 기반으로 하여 시스템이 달성하고자 하는 생산량 최대화, 비용의 최소화 등과 같은 목적 달성을 위한 초기해를 도출한다. 이를 통하여 FrMS 목적모델은 시스템의 최상위 목적부터 하위 세부목적을 설정하고 이를 달성할 수 있도록 하는 토대를 제공해줄 수 있을 것이다. 제안된 FrMS 목적모델은 분산형 지능시스템에서 최종목적의 변화에 따른 생산시스템의 변화 요구에 유연하게 대처할 수 있는 토대를 제공해 줄 수 있으며, 나아가 시스템에 요구될 수 있는 다양한 목적에 대한 신속한 대처를 가능하게 해줄 수 있을 것이다.

2. 관련 연구

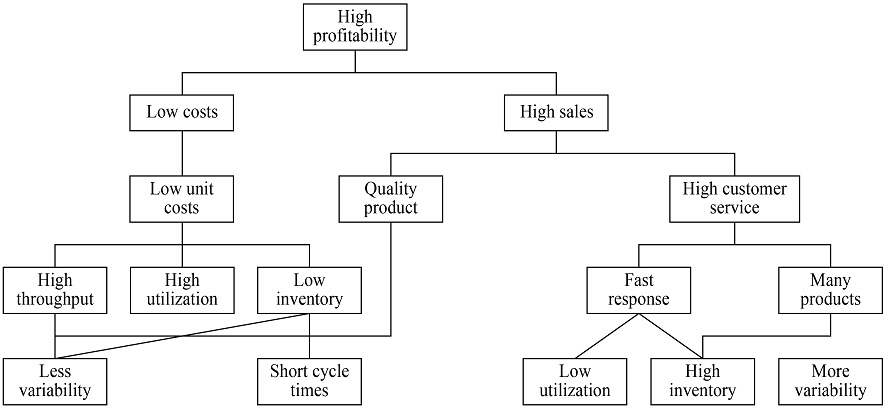

Monden(1993)은 생산시스템의 각 목적과 목적을 이루기 위한 행동(Activities)에 대한 관계를 정의하였으며 생산시스템의 최종 목표는 이익의 최대화와 비용의 최소화라고 하였다. Son and Park(1987)과 Craig and Harris(1973)의 생산시스템 평가 방식에 대한 연구에서 생산시스템의 가장 주요한 목적은 비용(Cost)의 감소로 볼 수 있으며 대부분의 평가 항목 역시 비용과 관계된 항목으로 이루어져 있다고 하였다. 특히 Son and Park(1987)의 생산시스템의 평가 방식 연구에서는 비용의 감소를 위한 주요한 목적을 생산성(Productivity), 품질(Quality), 유연성(Flexibility) 등 3가지로 분류하였다. Hopp and Spearman(1996)은 생산시스템의 목표를 계층적으로 분류하였으며 생산시스템의 최상위 목표를 <Figure 1>과 같이 이익(Profitability)의 최대화라고 규정하였다.

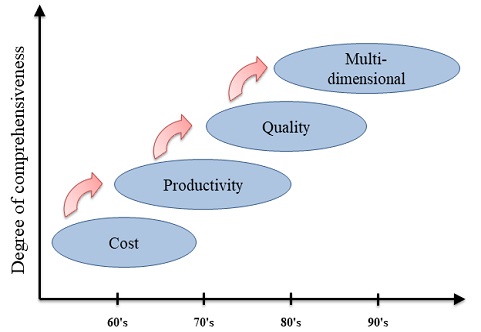

Nagalingam and Lin(1998)은 자동화 생산시스템(Automated Manufacturing System) 및 컴퓨터 통합 생산시스템(Computer Integrated Manufacturing System)의 효율성 향상을 위하여 생산시스템의 최상위 목표를 AHP(Analytic Hierarchy Process)로 분석한 결과, 직접 및 간접비용의 감소, 생산 및 노동력 관련 생산성의 향상, 비즈니스 전략 등 3가지를 주요한 목표로 도출하였다. Park and Kim(1995)의 생산시스템 평가 방법론은 경제적 관점에서 접근하고 있으며 따라서 생산시스템의 목적은 이익의 최대화와 직결된다고 하였다. Cochran et al.(2002)는 생산시스템의 디자인을 위한 분해 접근법(Decomposition Approach)에서 생산시스템의 최상위 목표는 판매량의 최대화, 생산 비용의 최소화, 생산시스템의 수명주기에 따른 투자의 최소화, 가치가 발생하지 않는 부분에 대한 비용 제거를 가장 주요한 목표로 설정하였다. Troxler(1989)는 전통적 생산시스템의 목적에 입각하여 생산시스템을 평가하기 위하여 적합성(Suitability), 역량(Capability), 퍼포먼스(Performance), 생산성(Productivity) 등 네 가지의 목적과 하위에 24개의 주요성과지표를 구성하였다. Narasimhan and Jayaram(1998)은 실제 제조기업의 목적을 분석하고 결정하기 위한 개념적 프레임워크(Conceptual Framework)를 구축하는 과정에서 제조기업이 실제로 추구하는 목적은 비용, 품질, 안정성(Dependability), 유연성(Flexibility)으로 규정하고 주요한 4가지 목적을 보조할 수 있는 주요평가지표는 프로세스 개선(Process Improvement), 공급 관리(Supply Management), 인적자원 관리(Human Resource Management), 기술 및 혁신(Technology and Innovation) 등을 제시하였다. Corbett(1998)은 생산 전략의 주요성과지표(Key Performance Indicator; KPI)는 품질(Quality), 인벤토리(Inventory), 유연성(Flexibility), 그리고 운송(Delivery)이라고 정의하였다. Cahill and O’kelly(1998)는 고등 생산시스템의 생산성 측정을 위하여 제품 가격(Product Prices), 단위 원가(Unit Costs), 시설 이용률(Utilization of Facilities), 시설 생산성(Productivity of Facilities), 고정 및 운전 자본 요소(Fixed and Working Capital Elements of Capital Resources) 등 다섯 가지 주요성과지표를 사용하였다. Jose et al.(1999)는 생산시스템에서 가장 상위에 있는 다섯 가지 주요성과지표를 수익성(Profitability), 사양 적합성(Conformance to Specifications), 고객 만족도(Customer Satisfaction), 투자 수익률(Return on Investment), 그리고 자재 및 간접비용(Materials/Overhead Cost)으로 정의하였으며 가장 하위에 있는 성과지표를 효율성, 품질, 기술력(Technical Competence), 유연성, 혁신, 속도, 그리고 역량으로 분류하였다. Ahmad and Dhafr(2002)는 생산시스템의 주요성과지표를 안전과 환경(Safety and Environment), 유연성, 혁신, 퍼포먼스, 품질, 안전성 등 6가지로 분류하였으며 안정성은 고객 불만(Customer Complaints), 고객에게 제품을 정시 배달(On-time-in-full Delivery to Customer), 공급자로부터 원재료 정시 수령(On-time-in-full Delivery from Supplier), 전체 장비 효율성(Overall Equipment Effectiveness) 등과 같은 주요성과지표로 구성되어 있다. 정량적인 성과지표를 활용한 평가 방법론이 아니라 설문지에 의한 정성적인 성과지표를 포함한 평가 방법론이다. Yurdakul(2002)은 생산시스템의 목적은 이익의 최대화(Maximize Profit)이며 이를 달성하기 위해서 안전성, 시간, 유연성, 품질, 비용 등 네 가지 주요성과지표를 활용할 수 있다고 하였다. 각 주요성과지표는 하위 성과지표를 가지고 있으며 경쟁 전략(Competitive Strategy)과 함께 AHP(Analytic Hierarchy Process)를 활용하여 생산시스템에 이익을 최대로 할 수 있도록 하였다. Sheu and Peng(2003)은 생산시스템을 평가하기 위해서 퍼포먼스 성과지표와 결정 요인(Determinants) 두 가지 지표로 구분하였으며 각 지표는 공장 수준(Plant-level), 라인 수준(Line-level), 스테이션 수준(Station-level) 등 생산시스템의 목적에 따라 단계를 구분하였다. Cordero et al.(2005)은 생산시스템의 퍼포먼스 성과지표를 고객 만족, 제품 품질, 주문시부터 최종 제품까지 걸리는 생산 시간(Speed in Completing Manufacturing Orders), 생산성, 제품 라인의 다양성(Diversity of Product Line), 그리고 유연성으로 분류하였다. Hon(2005)은 <Figure 2>와 같이 생산시스템의 평가를 위한 프레임워크 및 새로운 평가 항목을 제시하였다. 제시된 주요 평가 항목은 단지 생산시스템의 평가에 국한되지 않으며 기업 전체의 평가 항목에 가깝다. Golec and Taskin(2007)은 경쟁전략에 속한 혁신, 주문 제작(Customization), 제품 확산(Product Proliferation), 가격 감소(Price Reduction)와 비용, 유연성, 품질, 속도, 안정성 등 다섯 가지 지표로 생산시스템의 목적을 정의하였다. 다섯 가지 지표는 각각 하위 지표와 47개의 측정 지표를 가지고 있다. Yang(2013)은 생산 프로젝트의 성공 및 평가를 위한 방법론 개발에서 최종 목적은 운송(Delivery), 품질, 비용, 프로젝트 생산으로 정의하였다.

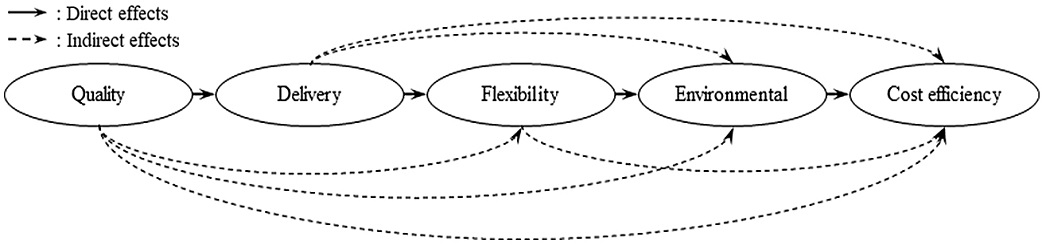

Avealla et al.(2011)은 생산시스템의 역량을 측정하기 위하여 <Figure 3>과 같이 성과지표는 서로 어떠한 관계를 가지고 있는지 서로 어떠한 영향을 미치는지 분석하였으며 분석 결과, 품질은 운송에 직접적인 영향을 미치며 생산시스템의 유연성, 환경적 요소, 비용 효율성에 간접적인 영향을 미치는 것으로 판단되었다. 또한 운송은 생산시스템의 유연성에 직접 영향을 미치며 환경적 요소와 비용 효율성에 간접적인 영향을 미치는 것으로 판단되었다. 생산시스템의 유연성은 환경적 요소에 직접적인 영향을 미치며 비용 효율성에 간접적인 영향을 미치는 것으로 판단되었으며 환경적 요소는 비용 효율성에 직접적인 영향을 미치는 것으로 판단되었다.

Fisher and Nof(1987)는 지식기반 전문가 시스템(Knowledge-based Expert System)을 활용하여 생산시스템을 경제적 측면에서 평가 및 분석하는 방법을 제안하였다. Jain et al.(2011)은 생산시스템의 퍼포먼스 측정을 위하여 DEA(Data Envelopment Analysis)를 사용하였으며 조립라인 생산(Assembly Line Manufacturing)의 투입요소는 노동 시간(Labor Hours), 가동시간(Uptime), 원재료 비용(Material Costs), 공급비용(Supply Cost)으로 설정하였으며 산출요소는 제품의 수량으로 설정하였다. <Table 1>은 제 2장에서 서술한 생산시스템의 성과지표에 대한 기존 연구를 간략히 정리한 내용이다.

3. FrMS 목적모델

3.1 목적모델을 위한 생산시스템의 목적 도출 및 분류

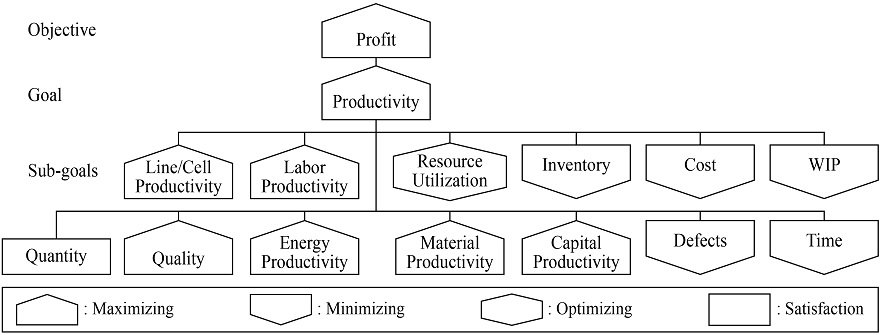

생산시스템의 일반적인 목적은 기존 연구에서 조사된 생산시스템의 목표와 FrMS의 참조 모델을 토대로 도출하였다. 제 2장에서 언급된 생산시스템을 평가하는 기존의 방법론들은 방식과 대상에 따라 다른 평가지표를 가지고 있지만 평가 대상의 최종 목적은 최대화(Maximization), 최소화(Minimization), 최적화(Optimization)로 볼 수 있으며 생산수량, 주문수량과 같은 경우에는 달성하기만 하는 목표로서 제약으로 볼 수 있다. 생산시스템이 추구해야할 목적 역시 이익의 최대화, 비용의 최소화, 자원 이용률의 최적화, 주문수량의 달성 등 기존의 4가지 구분 방법에서 벗어나지 않는다. 따라서 제안된 일반적 목적모델의 각 파라미터 구분법은 <Table 2>에서와 같이 기존의 방법과 마찬가지로 최대화, 최소화, 최적화 및 만족(Satisfaction)으로 구분할 수 있도록 하였다.

일반적인 목적은 <Table 2>의 파라미터를 토대로 하여 계층적인 구조를 가지고 있으며 하위 목표는 <Table 3>과 같이 도출할 수 있다. <Table 3>은 제 2장에서 언급한 기존의 생산시스템 평가 모델 논문들을 참조하여 도출하였으며 일부 하위 파라미터가 혼용되는 이유는 생산시스템의 퍼포먼스 측정 및 목적의 설정에 따라서 다양한 파라미터가 쓰이며 일부는 중복되어 쓰이고 다양한 측정 방식 및 목적의 설정이 가능하기 때문이다. 즉 하위 파라미터는 상위 파라미터에 종속되어 있는 것이 아니며 파라미터를 측정하기 위한 4가지 방법(최대화, 최소화, 최적화, 만족)에 의해 분류된 파라미터와 같은 속성을 가지고 있는 파라미터로 묶어 놓은 것이다. 이와 같이 일반적 목적모델은 생산시스템의 목적 설정에 따라서 하위 파라미터의 이동이 가능하다. 이윤의 최대화를 기업과 생산시스템의 궁극적인 목표로 설정한다면 생산시스템이 선택할 수 있는 현실적인 목적은 각 파라미터에 있다고 할 수 있다. 예를 들어 어떤 기업이 이윤의 최대화를 위하여 생산성을 최대로 하는 전략을 택하였을 때는 최종 목표에 따른 목적모델은 <Figure 4>와 같이 생산성의 최대화를 가장 상위 목적으로 하여 생산성의 최대화를 이루기 위해서 다른 목적들이 하위 목적(Sub-goal)으로 표현될 수 있다.

3.2 FrMS 목적모델의 특징 및 구조

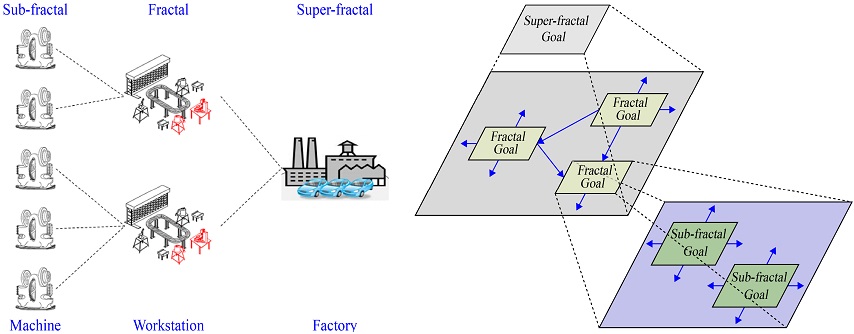

FrMS은 프랙탈 구조(Mandelbrot, 1982)를 생산시스템에 반영시킨 자가재구성이 가능한(Self-reconfigurable) 생산시스템이다. 예를 들면, 공장이라는 하나의 복합체에 다시 제조설비 단위로 구성된 프랙탈 복합체가 포함되어 있으며 개별 작업장은 다시 각종 생산설비로 구성된 순환적 구조를 지니고 있다. 각 프랙탈 복합체들은 각기 독립된 목적을 지닐 수 있다. 각각의 프랙탈은 최상위 목적의 달성을 위해서 각자 달성할 수 있는 서로 다른 목적을 가지는 것이다. 또한 프랙탈 복합체들은 동시에 각 목적간의 수평적인 관계 및 최종 목적의 변화에 따라 종속적인 연관관계를 가지고 최종 목적 변화에 따라서 목적을 변화시킬 수 있어야 한다. 따라서 FrMS의 목적모델은 FrMS의 구조적 특징과 유사한 다음과 같은 특성을 가지고 있다.

- • 자가 유사성(Self-similarity) : 단위 목적과 목적집합은 유사한 구조를 가지고 있다.

- • 자가 조직성(Self-organization) : FrMS의 목적모델은 외부 환경의 변화에 따라 스스로 상태를 변화시켜 최종 목적 및 목표를 변화시킬 수 있어야 한다.

- • 목적 지향성(Goal-orientation) : 각 단위 목적은 최상위 목적 및 목표의 변화에 맞추어 스스로 자신의 목적을 조정 및 변화시킬 수 있어야 한다.

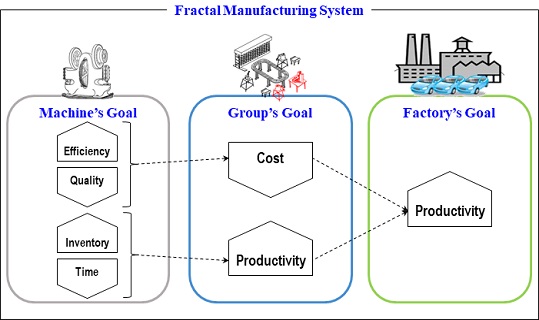

FrMS의 목적모델은 <Figure 5>에서 보는 것과 같이 최하위 유닛인 설비의 목적과 최상위 목적간 수직적인 구조를 지니고 있으며 같은 수준인 설비간, 설비 그룹 또는 라인간, 공장간 목적은 수평적 구조를 지니고 있다. <Figure 5>에서 설비의 목적은 하위 프랙탈, 설비 그룹 또는 라인의 목적은 프랙탈, 공장의 목적은 슈퍼 프랙탈로 나타내고 있으며 설비 그룹 또는 라인은 모듈 생산 파트 혹은 한 단위의 잡샵(Job Shop), 플로우 샵(Flow Shop)으로 정의될 수 있다. 슈퍼 프랙탈의 목적모델은 최상위 목적으로 표현된다.

대부분의 기존연구는 생산시스템의 최종목적이 정해져 있다는 것을 기본가정으로 한다. 일반적으로 생산시스템 또는 제조기업의 최종목적은 이익의 최대화이며 이를 달성하기 위하여 비용감소, 품질증가 등의 세부목표를 조정한다. 제조기업의 최종목적이 이익의 최대화에 있다는 것은 현실을 잘 반영한 기본가정이다. 하지만 최근 들어 필요에 따라 공적기업 및 공익을 위한 기업의 최종목적이 반드시 이익의 최대화가 아닌 경우도 생기기 시작하였으며 이익을 추구하는 사적기업에서도 때에 따라 최종목적의 변화에 대한 필요성이 보이는 일들이 생기기 시작하였다. 가령, Covid-19의 확산에 따른 마스크의 수요가 절대적으로 부족해지자, 기업은 공적영역의 요구에 따라 최단시간 내에 생산량의 극대화라는 목적을 가졌으며, 백신 역시 최단시간 개발 및 생산량의 극대화라는 목적을 가지고 백신의 개발 및 생산에 온 힘을 쏟고 있다. 따라서 기존의 생산시스템 최종목적에 대한 기본가정을 바꿀 필요성이 있으며 이를 통해서 다양한 최종목적을 설정할 수 있는 목적모델이 향후에는 더욱 필요할 것이라고 예상할 수 있다.

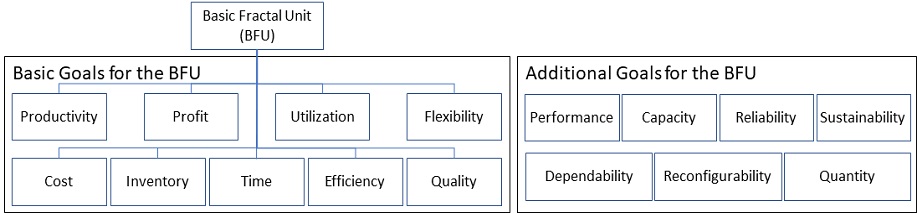

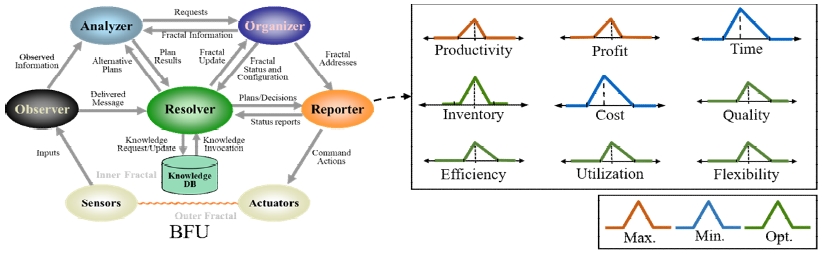

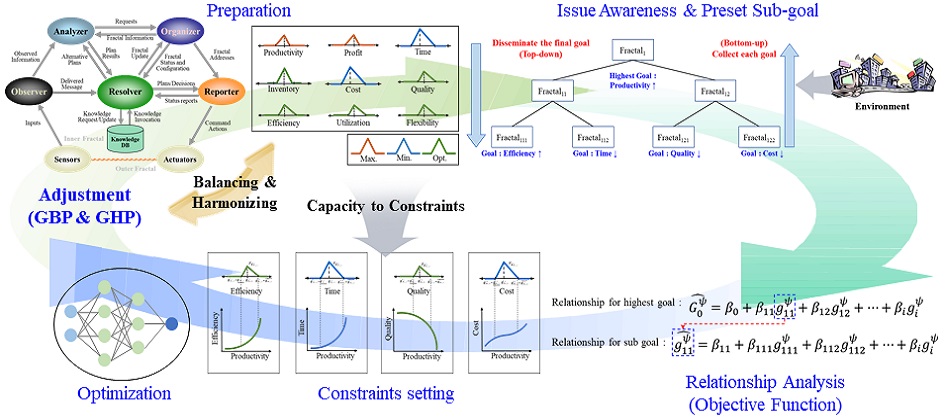

Ryu and Jung(2003)의 Basic Fractal Unit(BFU)은 FrMS를 구성하고 있는 가장 기본이 되는 유닛으로 Observer, Analyzer, Resolver, Organizer, Reporter 등 다섯 가지 기능 모듈로 구성되어 있으며 각 기능 모듈은 세부 기능을 담당하는 복수의 에이전트로 구현된다. 본 논문에서 제안하는 목적모델은 각 BFU에 적용할 수 있는 모델로 구성하였으며 이에 따른 자가 유사성 특성을 반영한 BFU의 목적모델의 기본구조는 <Figure 6>과 같다.

BFU의 목적모델을 구성하는 목적은 <Figure 6>에서와 같이 Productivity, Profit, Utilization, Flexibility, Cost, Inventory, Time, Efficiency, Quality의 9가지로 선정하였다. 이는 제 2장에서 조사된 결과를 바탕으로 다수의 연구결과에서 생산시스템 또는 기업의 주요성과지표 중 가장 주요하게 설정되었던 지표를 선정하였다. 추가목적인 Performance, Capacity, Reliability, Sustainability, Dependability, Reconfigurability, Quantity는 다양한 정의가 내려질 수 있거나 목적 자체가 최대화, 최소화가 아니라 충족(Fulfill) 요건에 해당하는 목적, 목적이 아닌 평가 및 시스템의 변화가능성을 보여줄 수 있는 것들이다. 추가목적은 필요에 따라 기본 목적모델에 포함할 수 있으며 본 논문에서 밝히지 않은 목적이라도 기업에서 필요하다면 추가하여 사용할 수 있다.

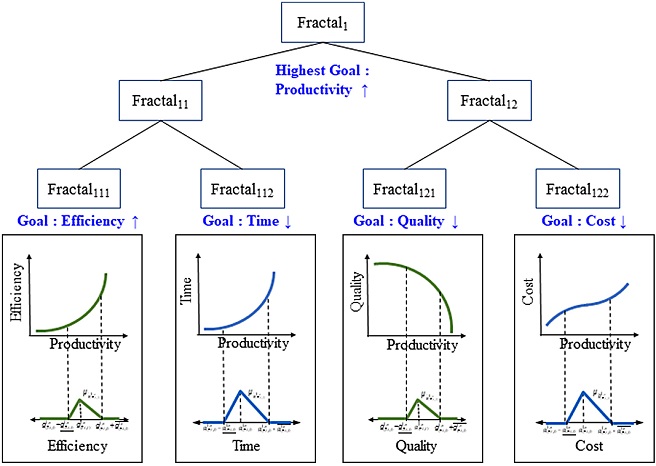

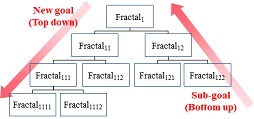

프랙탈 유닛의 목적모델은 프랙탈 유닛의 수준 및 크기에 관계없이 동일한 구조를 지니고 있다. <Figure 7>과 같이, 자가조직성과 목적지향성의 특성에 따라 최종목적이 설정되면 최종목적을 모든 프랙탈 유닛이 최종목적을 공유하고 이를 달성할 수 있도록 하위 목적이 설정된다. 즉, 최종 목적의 공유는 각 프랙탈이 어떠한 목적을 가질지 정하고 그에 맞는 행동을 하기 위한 이정표가 되는 것이다. 그리고 하위 프랙탈(Sub-fractal)은 목적 지향성(Goal-orientation) 특징에 따라서 상위 프랙탈 유닛에 의해 새로운 목적을 감지하여 각 프랙탈의 현재 상태(Status)에 따라서 최종 목적에 도달하기 위한 목적을 설정한다.

<Figure 7>에서와 같이 Efficiency 증가를 통한 생산성의 최대화를 위해서는 어떤 Efficiency를 증가시킬 것인지, 다른 BFU에서는 Time의 감소를 통해서 생산성을 증가시키고자 할 때 세부적인 지표가 필요하다. 따라서, 각 BFU의 목적 달성을 위해서는 <Table 4>와 같은 세부적인 핵심성과지표(Key Performance Indicator; KPI)가 필요하다.

3.3 FrMS 목적모델 메커니즘

FrMS의 기본 목적모델을 토대로 하여 각 프랙탈 유닛은 최종목적을 달성해야 한다. <Table 5>와 같이, 최종목적을 달성하기 위한 목적모델 메커니즘은 각 프랙탈 유닛간 목적모델을 구성하는 5단계로 구성되어 있다.

첫 번째 단계인 Preparation Step은 <Figure 8>과 같이 목적모델을 구성하기 전 각 프랙탈 유닛이 가지고 있는 능력(Capacity)을 조사하고 어느 정도 여유가 있는지 조사하여 이에 대한 정보를 보유하는 단계이다.

목적모델의 구성을 위해서는 프랙탈 유닛의 현재 능력과 최대 가용능력에 대한 정보가 반드시 필요하다. 본 논문에서는 Ryu and Jung(2003)가 제안한 프랙탈 유닛을 활용하며 프랙탈 유닛의 현재 정보는 Organizer에서 분석을 하며 Resolver가 최대 가용능력에 대한 정보에 대한 정보를 수집하여 두 정보를 Reporter가 Knowledge DB에 저장을 하게 된다. 각 세부목적의 가용능력은 <Figure 8>과 같이 퍼지 형태로 표현될 수 있다. 퍼지 수는 쉬운 이해를 위해 삼각 퍼지 수(Triangle Fuzzy Number)로 표현한다. 첫번째 단계의 최대가용능력은 Relationship Analysis와 Set the best goal model 단계에서 최종목적에 따른 초기 목적모델과 목적모델의 최적화에 활용된다.

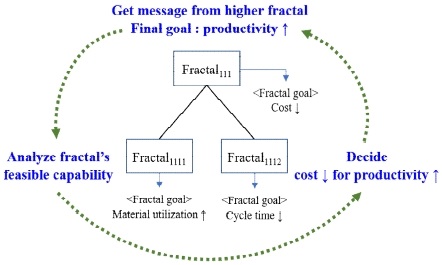

두 번째 단계인 Issue Awareness Step에서는 외부환경 또는 시스템에서 요구하는 최종목적을 인식하여 최상위 프랙탈 유닛이 새로운 시스템의 목적을 결정하게 된다. 외부환경에서의 정보는 Observer Agent가 인식해서 Analyzer Agent가 정보를 분석하여 Resolver Agent가 최종 목적을 결정하게 된다. 세번째 Preset Sub-goal Step은 최상위 목적을 하위 프랙탈에 전파하고 이를 달성하기 위해서 각 프랙탈 유닛이 하위 목적을 선정하는 과정이다. <Figure 9>는 Preset Sub-goal Step을 보여주고 있다.

<Figure 9>에서처럼, 상위 프랙탈 Fractal111이 최상위 목적인 Productivity 증가라는 목적을 인지하게 되면 이를 달성하기 위해 하위 프랙탈 Fractal1111과 Fractal1112에게 Productivity를 증가시킬 수 있도록 실현가능한 목적을 설정하라는 메시지를 보낸다. 메시지를 받은 Fractal1111과 Fractal1112는 최상위 목적을 달성하기 위해서 분석된 가용능력을 토대로 실현가능한 목적을 설정하고 이를 상위 프랙탈에 전달하게 된다. <Figure 9>에서는 자원 효율성(Material Utilization)과 사이클타임(Cycle Time)을 통해서 생산량(Productivity)을 증가에 기여하게 되며 상위프랙탈은 하위프랙탈 정보를 취합하고 상위 프랙탈에서도 달성할 수 있는 목적을 설정하여 이를 최상위 프랙탈에 전달하게 된다.

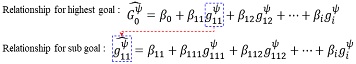

네 번째 단계인 Relationship Analysis에서는 모든 프랙탈의 하위목적을 토대로 각 목적간의 관계를 설정하게 된다. 목적간 관계는 식 (1)과 같이 Regression Model의 형태로 표현할 수 있으며 최종목적은 G, 하위목적은 g, i는 프랙탈 유닛의 일련번호, ψ는 각 목적모델의 실제 목적값으로 표현된다. 각 하위 목적은 보다 하위 목적의 집합에 대해서 Regression Model의 형태를 가진다.

- G= Highest goal for system

- g= Eachfractal’s goal

- β= Regression coefficient

- i= {1, 11, 12, …, 21, 22, 23, …, 111, 112, …, n} Fractal indicator(n = fractalID)

- ψ= {Prod, Prof, Util, Flex, Cos, Iven, Time, Effi, Qual, …}, Goal indicator

| (1) |

마지막 단계인 Set Best Goal Model Step에서는 Neural Network기반 최적화 기법을 사용하여 도출된 목적모델에서 최종목적을 달성한다. Preparation Step에서 도출된 각 세부목적별 Triangle Fuzzy Number를 기반으로 하여 최종목적과 각 세부목적간 관계에서 최적화 기법 적용 시, 제한조건(Constraint)은 <Figure 10>과 같다. <Figure 10>에서 Fractal111은 Sub-goal로 Efficiency를 선택하였으며 Fractal111의 가용한 Efficiency 증감의 폭이 최종목적 Productivity의 Constraint가 된다. 본 논문에서 제안하는 Neural Network기반 최적화 기법은 Gabriel et al. (2018)을 참조하였으며 필요에 따라 Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) 등 다른 휴리스틱 역시 적용이 가능하다.

4. 실험 및 결과

본 논문에서 제안된 인공신경망을 활용한 목적모델 도출 실험을 위해서 파이썬 3.8을 활용하였다. 실험을 위한 인공신경망의 구축에 있어서 실험데이터는 <Figure 10>과 같이 총 4개의 하위 프랙탈로 구성되어 있으며 2개의 하위 프랙탈이 하나의 상위 프랙탈을 구성하도록 하였다. 실험은 학습데이터 500건으로 학습을 시킨 후 검증 데이터 500건으로 예측값에 대한 적합도를 높여 인공신경망의 정확성을 높였다. 시스템의 최종목적은 Profits로 설정하고 학습 및 검증데이터에서 목적식을 도출하였으며 이를 토대로 초기해를 도출하였다. 신속한 학습이 가능하도록 신경망의 구조를 최대한 단순화하여 실험을 수행하였으며 5개의 입력 노드, 5개의 은닉 노드로 구성된 1개의 은닉층, 그리고 출력 노드는 1개로 구성하였다. 활성화 함수(Activation function)는 Sigmoid, Rectified Linear Unit, Hyperbolic Tangent 등 다양한 함수들 가운데 학습 정확도가 가장 높게 나왔던 Soft sign Activation Function을 사용하였다. 학습 횟수는 500번으로 설정하였다.

실험에 사용된 데이터의 지표는 총 6가지(Productivity, Efficiency, Utilization, Flexibility, Cost, Profits)이며 모두 정량적인 지표로 설정하였다. Profit을 제외한 독립변수 지표는 최소값을 0, 최대값을 1로 설정하였다. Productivity와 Efficiency는 프랙탈의 최대 생산량 및 최대 효율을 1로 설정하고 프랙탈이 멈춘 상태를 0으로 설정하였으며, Utilization은 프랙탈이 자원, 에너지 등 이용가능한 모든 자원을 완전히 활용하였을 때를 1로 설정하였으며 프랙탈이 멈춘 상태를 1로 설정하였다. 그리고 각 프랙탈의 최소 Utilization은 0.3으로 하한선을 두었다. Flexibility는 정량적인 지표로 표현하기 힘든 지표 중에 하나로 Equipment Flexibility, Product Flexibility, Process Flexibility, Partitionability, Adaptability, Extendibility, Multifunctionality 등 관련된 하위지표를 0과 1사이에서 정량적으로 변환한 후, 전체 Flexibility에 반영하였다. Cost는 각 프랙탈이 멈춘상태를 0으로 설정하고 최대 생산 및 효율을 달성한 프랙탈은 1로 설정하였다. 하지만 Cost의 경우에는 고정비가 존재하기 때문에 이를 제약식에 0.3으로 설정하였다. 목적모델의 목표인 종속변수는 Profits은 모든 프랙탈이 활동을 멈춰서 Profits가 없는 상태를 0으로 설정하고 최대 Profits는 2로 설정하였다.

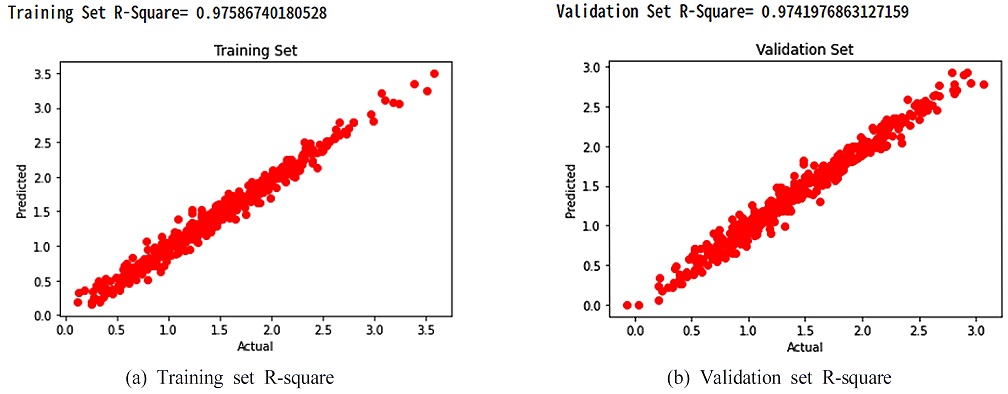

실험결과, <Figure 11>과 같이 학습의 정확도는 0.976, 검증의 정확도는 0.974였으며 신경망 자체의 에러값은 0.0092로 나타났다. 신경망을 활용한 회귀모델의 학습 및 예측과 같은 경우에는 R-square를 통한 회귀모델 예측의 정확성을 평가할 수 있으며 <Figure 11>과 같이 신경망의 예측값과 실제값의 일치율(정확도)이 0.97로 나타났음을 볼 때, 인공신경망 학습이 잘 되었다고 볼 수 있다.

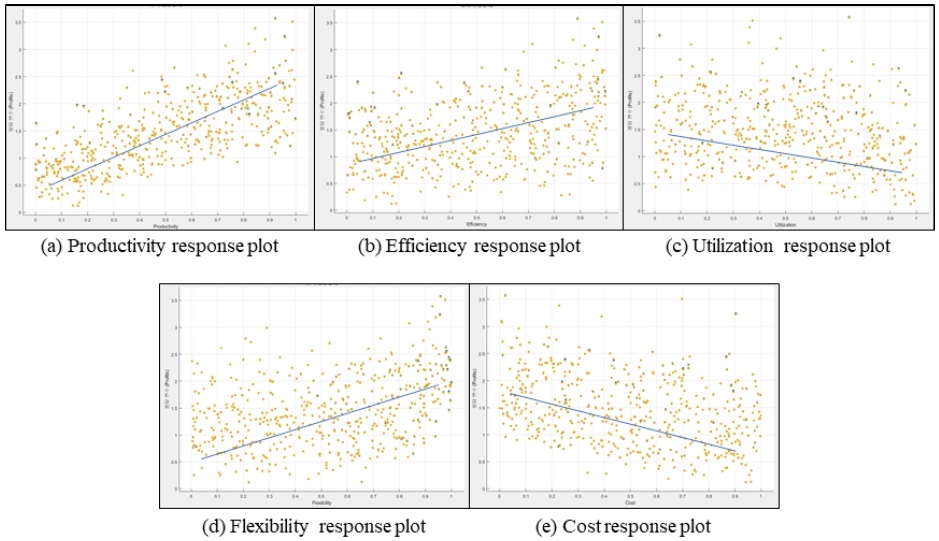

Matlab으로 도출한 각 독립변수와 종속변수간의 분포는 <Figure 12>와 같이 도출되었다. 독립변수 Productivity, Efficiency, Flexibility는 종속변수인 Profits에 양의 상관관계를, Utilization과 Cost는 음의 상관관계를 나타내고 있는 것을 확인할 수 있다.

일반적으로 최적해를 구하기 위해서는 목적식을 정확히 알고 있는 경우가 대부분이나 본 논문에서는 목적모델을 위한 목적식을 도출하여 최종적으로 1차적인 최적해를 구하는 것이 최종목표이다. 따라서, 학습된 데이터를 바탕으로 도출된 목적모델은 식 (2)와 같으며 <Figure 12>에서 확인한 것과 같이 Cost가 Profits에 가장 부정적인 영향을 미치고 있으며 Productivity가 가장 좋은 영향을 미치고 있는 것으로 도출되었다. Utilization의 경우에도 Profits에 부정적인 영향을 미치고 있는 것으로 확인되었는데 자원 사용량, 인력의 사용량(시간), 설비의 사용량(시간), 전력 사용량 등이 Cost에 일정부분 영향을 미치기 때문인 것으로 유추할 수 있다.

| (2) |

도출된 식 (2)를 바탕으로 최소비용 등의 간단한 제약을 설정한 뒤 도출된 1차적인 최적해는 <Table 6>과 같다.

목적식을 알 수 없는 Raw Data에서 독립변수가 다수인 다변량 다항 회귀 모델을 도출하는 것은 쉽지 않다. 하지만 이미 목적식을 알고 있다는 가정 하에 다항 회귀분석을 실시하였으며 도출된 1차적인 최적해는 <Table 7>과 같다. 목적식을 제외한 다른제약을 동일하게 설정하였으며 Linear Regression Model의 최적해와 비교하였을 때, Productivity가 줄어들었음을 확인할 수 있다. 또한 Non-linear Regression Model의 1차적인 최적해는 Flexibility를 감소시키고 Efficiency를 증가시켜 최종목적인 Profits에 도달하는 1차적인 최적해를 도출한 것을 볼 수 있다. <Table 6>과 <Table 7>의 1차적인 최적해를 바탕으로 도출된 Profits의 값은 Linear Regression Model이 1.898이며, Non-linear Regression Model이 1.833으로 약 0.065로 근소한 차이를 보이고 있다. 이와 같은 결과로 Non-linear Regression Model이 원래의 목적식인 Non-linear Regression Model과 근접한 결과를 얻을 수 있다는 것을 확인할 수 있다.

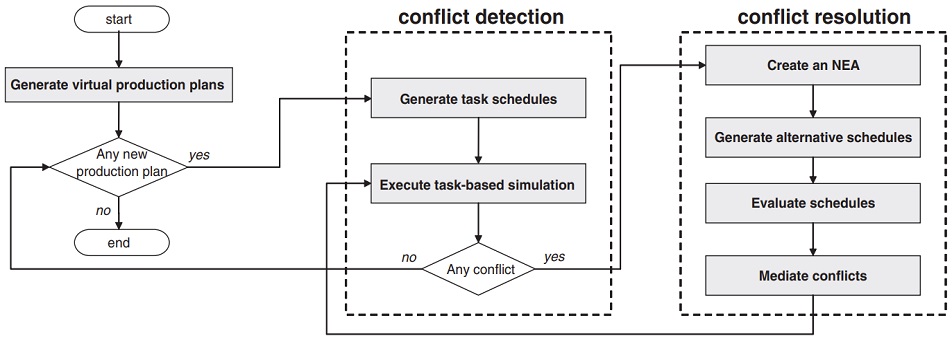

식 (2)에서 도출된 결과는 현재 상태에서 최상위 목적이 달성할 수 있는 초기해가 될 수 있다. 하지만 하위 프랙탈의 목적간 충돌 등은 고려되어 있지 않으며 세부목적간 충돌은 Shin et al. (2006)이 제안한 Goal-harmonizing Process(GHP)와 Cha et al. (2007)이 제안한 Goal-balancing Process(GBP)를 활용하여 해결한다. GHP는 <Figure 13>과 같이 작업(Task)기반의 시뮬레이션을 활용하여 각 프랙탈 목적간 충돌을 찾아내고 프랙탈간의 협상을 통하여 목적의 충돌을 해소하거나 완화시키는 역할을 한다. GBP는 각 프랙탈 목적간 충돌이 완화된 상태에서 각 프랙탈이 실제 작업환경에서 목적을 수행할 때, 각 프랙탈의 편향된 작업부하(Workload)를 감소시켜 시스템의 안정성을 확보하고 최종목적을 원활히 수행할 수 있도록 한다. GBP와 GHP 과정은 시스템의 최종목적에 대한 초기해에 대한 조정의 역할을 수행하지만 초기해 조정을 위해서는 각 프랙탈의 실제 작업에 대한 디지털트윈 형식의 시뮬레이션이 선행되어야 한다. 이 과정에서 실제 작업환경과 작업부하와 같은 외부적인 요소에 따라서 각 하위 프랙탈의 목적 달성률이 조정될 수 있다. 만약 Non-linear Regression Model의 최적해인 1.833이 이상적인 해를 가정한다면 Linear Regression Model의 초기 최적해인 1.898은 GHP와 GBP의 프랙탈 목적간 충돌과 작업부하를 고려하지 않은 최적해라고 할 수 있으며 GHP와 GBP를 통하여 최적해값으로 도달할 수 있다고 말할 수 있다. 목적모델을 포함한 생산시스템의 최적해 탐색 과정은 <Figure 14>와 같다.

5. 결 론

본 논문은 FrMS(Fractal Manufacturing System)의 목적 주도 기술을 위한 FrMS 목적모델을 제안하였다. 제안한 FrMS 목적모델 도출을 위하여 일반 생산시스템의 목적 및 목표, 생산시스템의 평가에 관한 기존 문헌연구를 바탕으로 생산시스템의 평가와 목표, 목적에 관한 파라미터 및 지표를 도출한 후, 이를 토대로 일반적인 목적 집합을 도출하였다. 도출된 일반적 목적 집합을 토대로 FrMS 목적모델을 도출하였다. FrMS 목적모델의 새로운 기준은 기업 또는 생산시스템 전체 목표를 나타낼 수 있는 목적과 각 프랙탈이 설정할 수 있다. FrMS 목적모델은 FrMS와 동일하게 세 가지 특징인 자가 유사성(Self-similarity), 자가 조직성(Self- organization), 목적 지향성(Goal-orientation)을 가지고 있으며 FrMS 목적모델은 생산시스템의 최종 목적에 따라 유연하게 반응할 수 있다는 장점이 있다. FrMS 목적모델에서 최종목적식은 통계적 기법을 활용하였으며 신경망을 기반으로 최적화를 달성할 수 있도록 제안했다.

본 연구에서 제시한 FrMS의 목적모델은 시스템의 최상위 목적부터 하위 세부목적을 설정하고 이를 달성할 수 있도록 하는 토대를 제공해줄 수 있을 것이다. 제안된 FrMS 목적모델은 분산형 지능시스템에서 최종목적의 변화에 따라 생산시스템의 변화 요구에 유연하게 대처할 수 있는 토대를 제공해 줄 수 있으며 나아가 시스템이 요구할 수 있는 다양한 목적에 대한 신속한 대처를 가능하게 해줄 수 있을 것이다. 또한 제안된 목적모델을 활용하여 생산시스템에서 도출되는 데이터를 통한 생산시스템 목표에 대한 분석 및 개선점 도출, 스마트 팩토리, Digital Twin 등과 접목을 통한 생산시스템 내부의 다양한 데이터를 통하여 생산시스템의 최적화를 수행하고자 할 때 이에 대한 초기해를 제공할 수 있는 토대가 될 수 있을 것이다.

하지만 일반적인 최적해를 찾기 위한 목적식을 먼저 도출하는 것이 우선되어야 하며 순수한 데이터를 통해서 비선형 회귀식에 가까운 목적식을 보다 정확하게 도출해야 한다. 이를 위해서 다변량 다항 회귀 모델(Multivariate Polynomial Regression Model), 비선형 회귀식 추정을 통한 오차가 최소화되는 목적식 도출에 대한 연구가 진행되어야 할 것이다. 또한 실험에 필요한 데이터는 스마트 팩토리를 포함한 생산시스템에서 생성되는 모든 데이터가 요구되기 때문에 현실성 있는 데이터를 확보하는 것에 대한 후속적인 조치가 필요하다.

Acknowledgments

이 논문은 부산대학교 기본연구지원사업(2년)의 의하여 연구되었음.

References

-

Ahmad, M. M. and Dhafr, N. (2002), Establishing and Improving Manufacturing Performance Measures, Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 18, 171-176.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0736-5845(02)00007-8]

- Attar, A. and Kulkarni, L. (2014), Fractal Manufacturing System-Intelligent Control of Manufacturing Industry, International Journal of Engineering Development and Research, 2(2), 1814-1816.

-

Avella, L., Vazquez-Bustelo, D., and Fernandez, E. (2011), Cumulative Manufacturing Capabilities : An Extended Model and New Empirical Evidence, International Journal of Production Research, 49(3), 707-729.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540903460224]

-

Brussel, V. H., Wyns, J., Valckenaers, P., Bongaerts, L., and Peeters, P. (1998), Reference Architecture for Holonic Manufacturing Systems : PROSA, Computers in Industry, 37(3), 255-274.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-3615(98)00102-X]

-

Cahill, E. A. and O’kelly, M. E. J. (1998), Productivity Measurement in Advanced Manufacturing Technology, International Journal of Computer-integrated Manufacturing Systems, 1(1), 18-24.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0951-5240(88)90006-7]

-

Cha, Y., Shin, M., Ryu, K., and Jung, M. (2007), Goal-Balancing Process for Goal Formation in the Fractal Manufacturing System, International Journal of Production Research, 45(20), 4771-4791.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540600787234]

-

Cochran, D. S., Arinez, J. F., Duda, J. W., and Linck, J. (2002), A Decomposition Approach for Manufacturing System Design, Journal of Manufacturing System, 20, 371-389.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6125(01)80058-3]

-

Corbett, M. L. (1998), Benchmarking Manufacturing Performance in Australia and New Zealand, Benchmarking Quality Management Technology, 5(4), 271-282.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/14635779810245134]

-

Cordero, R., Walsh, S. T., and Kirchhoff, B. A. (2005), Motivating Performance in Innovative Manufacturing Plants, The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 16, 89-99.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2005.06.005]

- Craig, C. E. and Harris, R. C. (1973), Total Productivity Measurement at the Firm Level, Sloan Management Review, 14(3), 13-29.

-

Fisher, E. L. and Nof, S. Y. (1987), Knowledge-based Economic Analysis of Manufacturing Systems, Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 6(2), 137-150.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6125(87)90037-9]

-

Villarrubia, G., De Paz, J. F., Chamoso, P., and De la Prieta, F. (2018), Artificial Neural Networks Used in Optimization Problems, Neurocomputing, 272, 10-16.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2017.04.075]

-

Golec, A. and Taskin, H. (2007), Novel Methodologies and a Comparative Study for Manufacturing Systems Performance Evaluations, Information Sciences, 177(23), 5253-5274.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2007.06.024]

-

Hon, K. K. B. (2005), Performance and Evaluation of Manufacturing Systems, CIRP Annual Manufacturing Technology, 54, 139-154.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-8506(07)60023-7]

- Hope, W. and Spearman, M. (1996), Factory Physics, First Edition Boston, Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

-

Jain, S., Triantis, K. P., and Liu, S. (2011), Manufacturing Performance Measurement and Target Setting : A data Envelopment Analysis Approach, European Journal of Operational Research, 214(3), 616-626.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2011.05.028]

-

Jose, A. F. B. G., Harry, B., and Frank, C. M. (1999), CI and Performance : A Cute Approach, International Journal of Operations and Productions Management, 19(11), 1120-1137.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/01443579910291041]

-

Lee, S., Kurniadi, K. A., Shin, M., and Ryu, K. (2020), Development of Goal Model Mechanism for Self-Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems in the Mold Industry, Procedia Manufacturing, 51, 1275-1282.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.10.178]

- Mandal, U. K. and Sarkar, B. (2014), Selection of Best Intelligent Manufacturing System (IMS) Under Fuzzy Moora Conflicting MCDM Environment, International Journal of Emerging Technology and Adcanced Engineering, 2(9), 301-310.

- Mandelbrot, B. B. (1982), The Fractal Geometry of Nature 1st Edition, Freeman, New York.

- Monden, Y. (1993), Toyota Production System : An Integrated Approach to Just-In-Time. Norcross, Georgia : Industrial Engineering and Management Press.

-

Nagalingam, S. V. and Lin, G. C. I. (1998), A methodology to Select Optimal System Components for Computer Integrated Manufacturing by Evaluating Synergy, Computer Integrated Manufacturing Systems, 11(3), 217-228.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0951-5240(98)00022-6]

-

Narasimhan, R. and Jayaram, J. (1998), An Empirical Investigation of the Antecedents and Consequences of Manufacturing Goal Achievement in North American, European and Pan Pacific Firms, Journal of Operation Management, 16(2-3), 159-176.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(97)00036-3]

- Okino, N. (1993), Bionic Manufacturing Systems, Proceedings of the CIRP Seminar on Flexible Manufacturing Systems Past-Present-Future, Peklenik, J. (ed.), Slovenia, 73-95.

-

Park, C. S. and Kim, G. (1995), An Economic Evaluation Model for Advanced Manufacturing Systems using Activity-based Costing, Journal of Manufacturing System, 14, 439-451.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6125(95)99916-2]

-

Renna, P. and Ambrico, M. (2011), Evaluation of Cellular Manufacturing Configurations in Dynamic Conditions using Simulation, International Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 56(9), 1235-1251.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-011-3255-0]

- Ryu, K. and Jung, M. (2002), Dynamic Modeling of Fractal-Specific Characteristics in Fractal Manufacturing Systems, Proceedings of the 35th CIRP-International Seminar on Manufacturing Systems, Korea, 444-450.

-

Ryu, K. and Jung, M. (2003), Agent-based Fractal Architecture and Modelling for Developing Distributed Manufacturing Systems, International Journal of Production Research, 41(17), 4233-4255.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0020754031000149275]

-

Ryu, K. and Jung, M. (2004), Goal-Orientation Mechanism in the Fractal Manufacturing System, International Journal of Production Research, 42(11), 2207-2225.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540410001661427]

- Ryu, K., Shin, M., and Jung, M. (2001), A Methodology for Implementing Agent-based Controllers in the Fractal Manufacturing System, Proceedings of 5th Conference on Engineering Design & Automation, U.S.A., 91-96.

-

Ryu, K., Yücesan, E., and Jung, M. (2006), Dynamic Restructuring Process for Self-Reconfiguration in the Fractal Manufacturing System, International Journal of Production Research, 44(15), 3105-3129.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540500465659]

- Seidel, D., Hopf, M., Prado, J. M., Garcia-Herreros, E., Strasser, T. D., Christensen, J. H., and Oblak, J. M. (1994), HMS-Strategies, The Report of HMS Consortium.

- Shin, M. and Jung, M. (2006), Fractal Manufacturing System(FrMS) based on Autonomous and Intelligent Resource Model(AIR-model), The 2006 KIIE Fall/KORMS Joint Spring Conference, KAIST, Daejeon, May 19-20, 348-353.

-

Shin, M., Mun, J., Lee, K., and Jung, M., (2009), r-FrMS : A Relation-Driven Fractal Organisation for Distributed Manufacturing Systems, Interantional Journal of Production Research, 47(7), 1791-1814.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540802036240]

- Shin, M. and Ryu, K. (2013), Agent-based Resource Model for Relation-driven Fractal Organization, ICIC Express Letters(An International Journal of Research and Surveys), 7(5), 1539-1544.

-

Shin, M., Ryu, K., and Jung, M. (2012), Reinforcement Learning Approach to Goal-Regulation in a Self-Evolutionary Manufacturing System, Expert Systems with Applications, 39(10), 8736-8743.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.01.207]

-

Shin, M., Cha, Y., Ryu, K., and Jung, M. (2006), Conflict Detection and Resolution for Goal Formation in the Factal Manufacturing System, International Journal of Production Research, 3(1), 447-465.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540500142845]

-

Sheu, D. D. and Peng, S. (2003), Assessing Manufacturing Management Performance for Notebook Computer Plants in Taiwan, International Journal of Production Economics, 84(2), 215-228.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(02)00428-0]

-

Tirpak, T. M., Daniel, S. M., LaLonde, J. D., and Davis, W. J. (1992), A Note on a Fractal Architecture for Modeling and Controlling Flexible Manufacturing Systems, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 22, 564-567.

[https://doi.org/10.1109/21.155958]

-

Troxler, J. W. (1989), A Comprehensive Methodology for Manufacturing System Evaluation and Comparison, Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 8(3), 175-183.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6125(89)90039-3]

-

Ueda, K. (1992), A Concept for Bionic Manufacturing Systems based on DNA-type Information. Human Aspects in Computer Integrated Manufacturing, Proceedings of the IFIP TC5/WG5.3 8th International PROLAMAT Conference, Japan, 853-863.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-89465-6.50078-8]

-

Ueda, K., Vaario, J., and Ohkura, K. (1997), Modeling of Biological Manufacturing Systems for Dynamic Reconfiguration, Annual CIRP-Manufacturing Technology, 46(1), 343-346.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-8506(07)60839-7]

- Valckenaers, P., Brussel, H. V., Bongaerts, L., and Wyns, J. (1994), Results of the Holonic Control System Benchmark at the KULeuven, Proceeding of the CIMAT Conference, New York, 128-133.

-

Warnecke, H. J. (1993), The Fractal Company : A Revolution in Corporate Culture, Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-78124-7]

-

Yang, L. (2013), Key Practices, Manufacturing Capability and Attainment of Manufacturing Goals : The Perspective of Project/Engineer-to-Order Manufacturing, International Journal of Project Management, 31(1), 109-125.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.03.005]

-

Son, Y. K. and Park, C. S. (1987), Economic Measure of Productivity, Quality, and Flexibility in Advanced Manufacturing Systems, Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 6(3), 193-207.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6125(87)90018-5]

-

Yurdakul, M. (2002), Measuring a Manufacturing System’s Performance Using Saaty’s System with Feedback Approach, Integrated Manufacturing Systems, 13(1), 25-34.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/09576060210411486]

이상일 : 동아대학교 경영정보학과에서 2009년 학사학위를 취득하고, 부산대학교 산업공학과 대학원에서 2011년 석사학위를 취득하으며 현재 동 대학원에서 박사과정에 재학 중이다. 관심 분야는 차세대 생산시스템과 디지털 생산시스템이다.

류광열 : 포항공과대학교 산업공학과에서 1997년 학사, 1999년 석사, 2004년 박사학위를 취득하였다. 2004년부터 한국생산기술연구원 선임연구원을 역임하고, 2008년부터 부산대학교 산업공학과 교수로 재직하고 있다. 연구분야는 스마트 팩토리, 스마트제조 관련 기술(AI, CPPS, AR/VR, IoT 응용 등), 제조데이터 분석 기술, 차세대 생산시스템과 디지털 제조혁신 기술 등이다.